Belgium has raised eyebrows by loosening Covid restrictions, despite the surging trend in new Covid positive test results there. This is notable because it bucks the trend in Europe.

From October 1, face masks will only be mandatory in crowded places. Currently masks are required in all public spaces, which is one of the most draconian mask mandates in Europe. The quarantine period will be reduced from 14 to 7 days, too, while its “bubble of five” (which determines how many people you can have close contact with) will be administered with greater flexibility. Plenty of restrictions remain, and at similar levels to other European countries, but overall a less hawkish strategy.

The government also announced that PCR tests (the dominant form of testing for Covid) will no longer be relied upon as a gauge of the prevalence of the virus, and instead the focus will be on the number of hospitalisations. False positives are a known problem in PCR testing, which is greatly exacerbated by ramping higher testing programs. This must have motivated the Belgium government’s pivot, alongside the resulting marked lack of correspondence between ballooning new cases and illness and mortalities in Belgium, which has been seeing daily Covid deaths range between zero and no more than seven since the beginning of September.

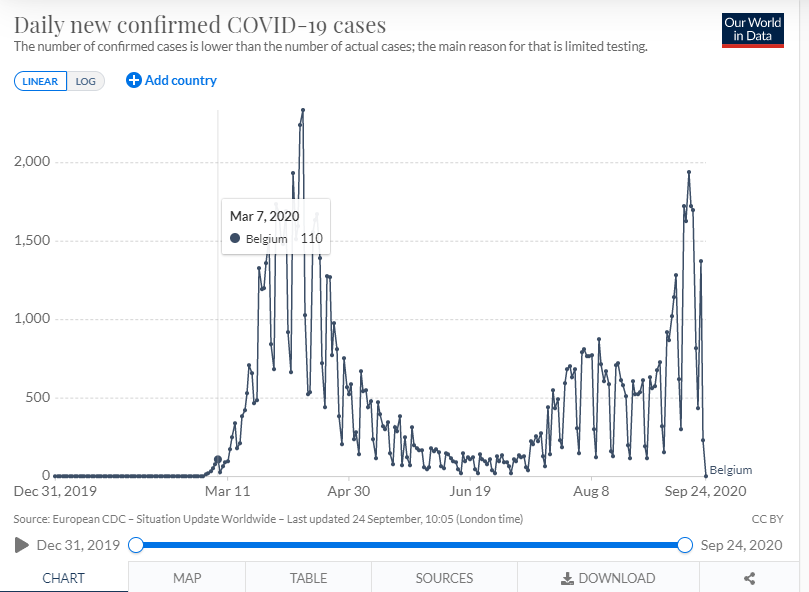

While the numbers of daily new cases in Belgium have returned to levels recorded during the March/April peak, ranging between about 1,500 and about 2,000 per day over the last week, hospitalisations are 10x lower than at the peak (based on the September 21 figure), while the average daily death count over the last week has been 64x lower than at the peak. Even allowing for a three-week lag between new cases and deaths, there is still a large degree of discordance between what’s happening now in Belgium, and across Europe, and what happened earlier in the year.

Hospitalisations and deaths have bumped higher in some European countries, most notably Spain, but they still remain far off peak-pandemic levels. Hospitalisation cases are predominantly those who are either at or over the age of average life expectancy in their respective countries; and the vast majority of the others are immunodeficient due to pre-existing disease.

The ‘be-very-afraid’ hypothesis, which sees Covid as remaining a major public health risk, and sees vaccination as the only way to save the day, still dominates government thinking in Europe outside Sweden, though the population immunity hypothesis (which, aside from Sweden, has many advocates in the medical science world, at least among those who don’t have ties with pharmaceutical companies) may be starting to get a look in.

Many advocates of the population immunity hypothesis point to the ‘casedemic’ that was seen in the 2008-09 H1N1 flu (aka swine flu) pandemic, where, after the actual public health impact had occurred, massively increased testing into the following 2009-10 winter season yielded a massive rise in cases but not a corresponding rise in illness/deaths. That casedemic, which academics in this school of thought are touting as the first ever casedemic, nonetheless caused a policy overreaction.

There is a certain unintended alchemy behind this modern phenomenon of a casedemic. The potion includes: a rate of false positive results in virus tests, caused by tests not being able to distinguish between leftover viral ‘fragments’ from a past infection and actual live infection; so-called functional immunity, where people are infected for a second time but recover rapidly, usually without symptoms; and, applicable in the prevailing circumstance, tests that mistake other coronaviruses for SARS-CoV-2 (a quarter of common colds are coronaviruses). The magic then happens as these vectors are drawn into play when a testing program is ramped up after an emerging and virulent viral pathogen has already taken its first swipe at the population, and after community immunity has built up.

Could we be witnessing ‘casedemic number 2’?

Click here to access the Economic Calendar

Andria Pichidi

Market Analyst

Disclaimer: This material is provided as a general marketing communication for information purposes only and does not constitute an independent investment research. Nothing in this communication contains, or should be considered as containing, an investment advice or an investment recommendation or a solicitation for the purpose of buying or selling of any financial instrument. All information provided is gathered from reputable sources and any information containing an indication of past performance is not a guarantee or reliable indicator of future performance. Users acknowledge that any investment in Leveraged Products is characterized by a certain degree of uncertainty and that any investment of this nature involves a high level of risk for which the users are solely responsible and liable. We assume no liability for any loss arising from any investment made based on the information provided in this communication. This communication must not be reproduced or further distributed without our prior written permission.