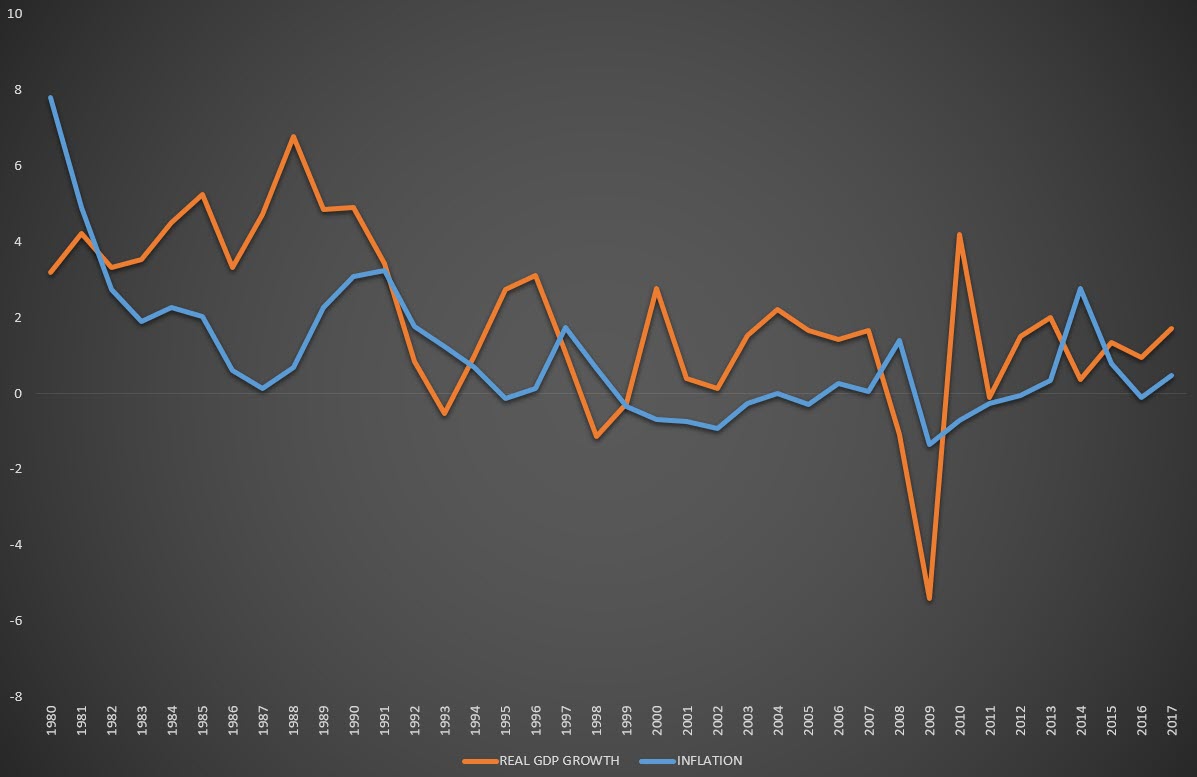

Japan has become, over the course of the past 30 years, an economics case study. Starting in the late 1980s, the country experienced an asset price bubble in 1986-1991, during which land prices rose by a staggering 150%, aided by loose economic policy as interest rates were actually reduced during the bubble years. Allowing for more demand came in handy for the aggressive bank lending behaviour observed during the period, leading to huge growth rates, as high as 6.8% in 1988, as a result of the increase in spending. As usual, after every sharp increase comes an even sharper drop as the JPN225 plunged more than 30% in the course of a year (1991).

The economic situation in Japan got more complicated over time. As a result of the burst, real GDP grew by 0.8% in 1992, compared to 3.4% in 1991. From 1993 onwards came a weird era when GDP grew and declined over a protracted period of time. From 1993 to 2007, average GDP growth was 1.2%, albeit ranging from -1.1% in 1998 to 2.7% in 1995. Ironically, just when businesses had managed to adjust their balance sheets to the large amount of debt accumulated over the bubble period, the economy was strongly hit by the global financial crisis, where it registered large declines in GDP.

The Lost Decade

The GDP situation during the global financial crisis varied across many countries in the world. Nonetheless, Japan posed a unique situation due to a number of reasons: first, as GDP declined the unemployment rate did not increase by much, reaching a maximum of just 5.4% in 2002. Second, while GDP averaged 1.2%, inflation averaged just 0.1%, moving between positive and negative figures throughout the period. This rather peculiar situation was attributed (namely by Nobel laureate Paul Krugman) to the stagnation in Japan’s population, which however appears a rather odd explanation: the country’s population increased by approximately 5.7% during the 1986-2007 period, which does not compare unfavourably to 5.9% for Germany, a country which never registered a negative inflation rate. A possible way of supporting this argument would be to claim that the country’s labour force and working age population (15-64) shrunk during the period, but again the same thing happened in Latvia and Georgia, where no inflation issues were observed.

Other policy actions (and in-actions) were also blamed for Japan’s bad performance, most popular among them BoJ’s unwillingness to maintain interest rates low for long or pursue quantitative easing policies and the lack of fiscal stimulus on the government side. The latter again appears to be non-reason given that fiscal debt increased from 63% of GDP in 1992 to 131% in 1999 and more than 200% in 2009. At the moment, fiscal debt stands at 236% of GDP and is the largest among all developed nations. The point commentators make is that fiscal policy was not continuously pushing the economy, even though this appears not to fully capture the essence of the country’s situation, given that spending continued to increase; despite a pause in government investment (which only took effect after 1996, at which point GDP was already positive and growing at 3%), tax revenue declined in the first years of the crisis and then remained relatively stable, assisted by generous tax cuts in the 1994-1995 period, and an overall reduction in corporate taxation.

The monetary argument also appears misplaced: data suggest that the interest rate declined to near-zero levels by 1998, which was, theoretically, the limit of monetary policy. Even if this was a liquidity trap, i.e. a situation where the interest rate cannot be further lowered so that it can affect consumer behaviour, then the argument would still not hold given that the policy response to such a situation would be to increase fiscal spending (something that had already happened) so as to boost inflation. The same holds with the Yen exchange rate, given that there appears to be no correlation between its evolution and the Japanese GDP and inflation path. Thus, the resurface of Japanese problems was mostly due to the fact that the economy could not sustain itself at the end of the fiscal and monetary stimulus programmes.

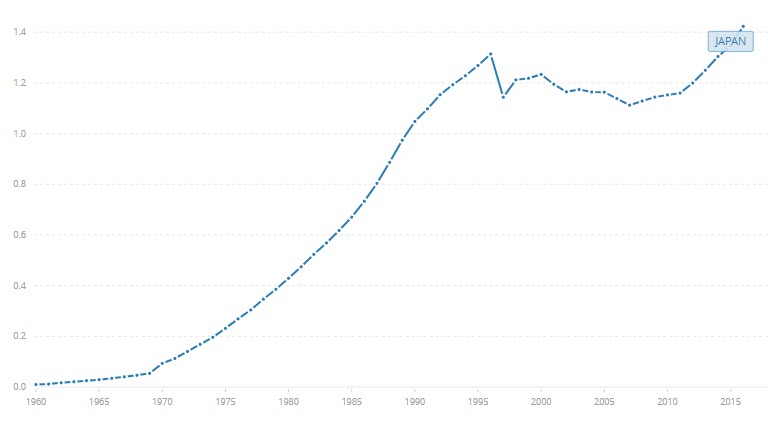

What was the issue then? Government policy was expansionary, the Japanese were actually saving a lower percentage of their income than before, foreign money was flowing into the country, and the Central Bank was not only printing money, it was also financing the government’s fiscal actions. Thus, the only thing that’s left is bank lending. Ironically, bank lending continued to increase until 1996 (as a percentage of GDP), after which it started a long decline, which did not end until 2011. Let’s put it in context then: government investment increased until 1996 and, assuming that the economy had picked up, stopped easing. The plan backfired because banks appear to have changed their minds with regards to lending.

Source: World Bank

Why was that? The answer is pretty simple and expected: bad loans. Bank lending soared during the bubble period, increasing by a staggering 71% during the 1980-1986 period, followed by another impressive 57.3% increase from 1986 to 1992. As expected, the bursting of the bubble brought trouble to loans which were mainly related to the housing/real estate sector, even though this was just an accident waiting to happen. As such, non-performing loans (NPLs) increased, threatening to eat up the banks’ capital and not leaving them any room to boost lending, despite two large bank recapitalization programs by the Japanese state, after the initial estimations of the banking sector’s need for capital were proven to have been very low. The increase in NPLs persisted until 2001, at which point they started to decline, but it was not until 2005 that they stabilised at a low, sustainable, point. Naturally, bad experience with NPLs makes banks very wary of granting more loans, whereas people also decide that banks are not willing to extent credit to them, making the whole communications channel break down. Add bad timing to this, as the global financial crisis erupted just two years later and then we get a full idea of why Japan’s problems have persisted until now.

Abenomics

In 2012, a political regime-switch took place, Shinzo Abe became Japan’s Prime Minister and vowed to take the country out of its 20-year slump. Abe had three main targets for his economic programme. The first was to push the Yen lower via expansionary monetary policy (quantitative easing), in order to boost exports. The policy didn’t work out as expected, given that most large companies either pocketed the difference or had already moved their plants abroad. In addition, the Yen depreciation also increased costs for import-reliant businesses and hence prices, hurting purchasing power.

Then Abe vowed to expand fiscal policy, by announcing large infrastructure expenditures, which were supposedly going to be offset by a 10% increase in the sales tax in 2014. This idea also proved to be not that good as GDP growth for the year dropped to 0.4%, and the economy faced a small recession. The economy has improved since the registering higher growth rates. The final target for Abe’s programme was to push structural reforms, which he has succeeded in thus far. Nonetheless, how much impact these reforms will have on the economy is still an issue of uncertainty.

To Abe’s defense, even if he did not manage to achieve much (and may have actually worsened the economic outlook), he was the first to fully commit to reviving the economy. This assisted in greatly improving the outsiders’ view of the Japanese economy and its growth prospects, especially as the US, which followed similar policy responses, had managed to exit the financial crisis. In line with Abe’s efforts, BoJ decided to further lower interest rates to negative territory in 2016, in the expectation that it would help boost private investment. Similar to the European experience, the move did not have the expected effects on investment, which continued on the same trend, other than more cash being used for real estate deals.

What’s the Outlook Then?

As discussed above, things appear to have changed now. Domestic credit has been increasing over the past years, GDP has been growing steadily, and inflation has been trending upwards for the first time since 2014. Can the Japanese economy sustain growth and positive inflation this time? In 2014, inflation surged above 2%, but this surge appeared to be a one-off event mainly attributed to the sales tax increase. Still, this time, Japan appears to have managed to slowly push itself into positive ground and, at least at this point, there appears to be very little reason for it to fall back. In addition, private investment appears to be continuing to increase to levels not observed since 2006, and bank credit to the private sector continues to increase. Even more impressively, imports have also been increasing since 2017, with only a minor glitch in April, supporting the view of higher domestic consumption.

To sum up, can Japan continue its growth? Japanese banks are much better capitalized than any time in the past 20 years, and they appear to be granting more loans, as the growth rate of lending suggests. The revival of the credit channel from the supply side (banks), along with the boost in demand for credit as a result of low interest rates, is expected to continue boosting consumer spending and private investment. Thus, the short answer is yes, provided that BoJ does not hurry to revise its interest rate policy and the government continues to pursue an, even mildly, expansionary fiscal policy just to maintain the perception of aiding the economy.

Click here to access the HotForex Economic calendar.

Want to learn to trade and analyse the markets? Join our webinars and get analysis and trading ideas combined with better understanding on how markets work. Click HERE to register for FREE! The next webinar will start in:

[ujicountdown id=”Next Webinar” expire=”2018/10/30 14:00″ hide=”true” url=”” subscr=”” recurring=”” rectype=”second” repeats=””]

Dr Nektarios Michail

Market Analyst

HotForex

Disclaimer: This material is provided as a general marketing communication for information purposes only and does not constitute an independent investment research. Nothing in this communication contains, or should be considered as containing, an investment advice or an investment recommendation or a solicitation for the purpose of buying or selling of any financial instrument. All information provided is gathered from reputable sources and any information containing an indication of past performance is not a guarantee or reliable indicator of future performance. Users acknowledge that any investment in FX and CFDs products is characterized by a certain degree of uncertainty and that any investment of this nature involves a high level of risk for which the users are solely responsible and liable. We assume no liability for any loss arising from any investment made based on the information provided in this communication. This communication must not be reproduced or further distributed without our prior written permission.