In a recent speech, Peter Praet, the European Central Bank’s Chief Economist suggested that “TLTROs have been a very useful tool to deal with impairments in the transmission of monetary policy”. The acronym stands for Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations and means that the ECB will provide funding to banks, in the form of longer-term loans, lasting up to four years instead of the usual overnight lending, linked to their loans to non-financial corporations and households.

In essence, the more loans banks give to non-financial corporations and households, the more they can borrow from the ECB. Banks will essentially be the mediators of ECB funding, and will channel the funds offered to them to businesses and households. Other than the fact that banks collect commission in the form of bank charges et cetera, it is even more profitable as the ECB money will be offered to them at a much lower interest rate compared the one they would have otherwise used to fund the same loans. Thus, the higher the amount of TLTROs a bank receives the more likely it is to increase its earnings in the coming years. Naturally, this does not come at no cost: higher lending could lead to lending to people with bad credit histories but, at least in theory (and definitely not always in practice), banks should lend prudently.

Departing from the prudence argument, the bigger question is whether banks actually need this additional funding. Just a month after the end of the Quantitative Easing programme, the ECB deciding that banks need more liquidity appears to be rather odd. The European Banking Authority (EBA) published a report in October, commenting that the average Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) in December 2017 stood at 145%, while all banks passed the 80% and 100% minimum levels, under different definitions. This means that for every Euro of loans a bank has, 1.45 Euros of deposits (or other liquid assets) exist. Put simply, if banks want to lend more, liquidity is not one of the factors restricting loan growth.

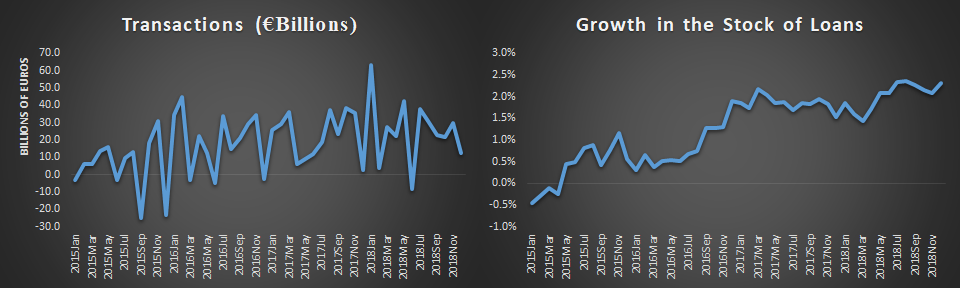

The Figure above supports this view. Using data from the European Central Bank, the growth in the stock of loans in the Euro Area appears to be on an increasing trend as of mid-2015, currently growing at 2.5% y/y. Similarly, transactions in loans, meaning the pure amount of ins and outs of the loans stock (e.g. excluding any FX effects, or interest accrued), also shows a positive image, with both an upwards trend and large positive numbers indicating more loans.

The real issue is that the ECB is currently in hubris mode. By believing that they could influence bank behaviour with QE, with research providing vague “success justifications”, they somehow appear to have come to the conclusion that the banking sector can be seen as the cure for all that is wrong. Even though the QE programme mainly lowered bond yields, raised bank shares, and “anchored inflation expectations” (as if they ever deviated significantly) this did not assist the troubled periphery countries, as they did not possess the suitable rating for meeting the QE eligibility criteria. Furthermore, they could not even benefit from lower yields as they were fiscally constrained. Countries were pushed to do reforms (some of which were of course much required) but, this had, of course, nothing to do with the banking sector.

Furthermore, policymakers spent years promoting the idea that decreasing current account deficits, and even more so, emphasising that countries should aim for trade surpluses, promoting Germany as the prime example of this strategy. Ironically, the fact that not all countries in the world can have surpluses was never a consideration.

The above mercantile policy backfired as soon as the world entered a trade war era. As much as developed countries do not like to admit it, they are all dependent on the United States and its over-consumption, also known as trade deficit, to sell their goods and services. The moment the United States tries to control trade, large exporters will suffer. In a case of ascertaining the above, this is what is happening to Germany, which is fighting to avoid recession, partly a result of high dependence on the US and partly due to the overall slowdown in world economic growth. A similar situation is also happening in the Netherlands, which records a reduction in 2018 GDP and also boasts of high exports.

This is not a situation that more lending will cure. Loan-to-GDP ratios are already high enough in the European Union, standing at 95.4% of GDP in 2017, lower than the 117% in 2009, but still high enough to potentially cause problems if banks are forced to follow an aggressive lending policy. Overall, solving a global problem with a local, unrelated, solution is not likely to be successful, especially as the TLTRO solution actually jeopardizes macroeconomic stability.

Markets-wise, a re-institution of TLTROs should, in theory, promote higher lending growth in the Euro Area, increasing the supply of money, with the corresponding effects on the Euro. At the same time, higher growth is not something which is expected to be achieved, certainly not from the exporting sector which will still be prone to international developments; however, some firms which focus on the domestic market are likely to benefit.

Click here to access the Economic Calendar

Dr Nektarios Michail

Market Analyst

Disclaimer: This material is provided as a general marketing communication for information purposes only and does not constitute an independent investment research. Nothing in this communication contains, or should be considered as containing, an investment advice or an investment recommendation or a solicitation for the purpose of buying or selling of any financial instrument. All information provided is gathered from reputable sources and any information containing an indication of past performance is not a guarantee or reliable indicator of future performance. Users acknowledge that any investment in FX and CFDs products is characterized by a certain degree of uncertainty and that any investment of this nature involves a high level of risk for which the users are solely responsible and liable. We assume no liability for any loss arising from any investment made based on the information provided in this communication. This communication must not be reproduced or further distributed without our prior written permission.