In a recent post, we have defined what inflation is and how it affects exchange rates. In short, inflation means that the supply of currency increases, which suggests that the price of currency (i.e. the exchange rate) declines. According to economic theory, the only things which should fundamentally matter for the determination of exchange rates relate to interest rate, inflation, and growth differentials. Having elaborated on how interest rate and inflation differentials affect the currency market, this post will now turn to the factors which have an impact on inflation, while a follow-up article will elaborate on how the determinants of inflation can be gauged through announcements of economic fundamentals. While the text below uses figures relating to the US, this is done for simplicity. Overall, the analysis is generic and it can be applied to a wide range of countries.

The Starting Point: A Closed Economy

Remember that inflation is calculated on the basis of a weighted basket of the most commonly bought goods and services in an economy whose price is tracked across time, usually on a monthly basis and it is called the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Like any other economic variable, inflation is determined by the forces of supply and demand. More specifically, these are defined as cost-push (supply) and pull (demand) inflation, details on which will be provided below. For simplicity, imagine now that we are observing a closed economy, i.e. an economy which does not have any interaction with the outside world. While practical examples of closed, self-sufficient, economies are rare in the real world, imagining an island with no way of coming or leaving it, provides a useful way to picture how such an economy would look like. Since no foreign capital can be injected into the country and no local capital can be sent abroad, the situation focuses on just domestic developments.

Demand-Pull Effects

The basic tenet of demand-pull effects is that higher demand for goods leads to higher prices. To put the word “pull” in perspective, think of it as consumers pulling the price up due to increased spending. However, spending needs to increase in the majority of the CPI goods in order to have an economy-wide and not just a specific-good effect. Let us now examine the determinants of higher demand in an economy.

To start with, a person working in a closed economy would, after some time at his job, wish to get a raise. If he gets the raise then this essentially means that this person will have more spending power, whilst the spending power of his boss will be reduced, as his profit will decline, all things equal. A higher wage cannot be counteracted with a higher price given that, as the purchasing power of the general populace remains the same, an increase in price would decrease the quantity sold. In such an economy, for one person to earn more money, it would necessarily mean that someone else would have to earn less, given that everything else is constant. To illustrate this, suppose that two bakeries exist in the country. If bakery 1 makes terrible bread then it will lose all of its customers, who will start buying from bakery 2. If total spending was, say, $100 per bakery, then after the deterioration in quality total spending would still be $200, only this time bakery 2 will get it all. Even in the case where bakery 2 decides to increase its prices, then this would mean that while its profit will increase, available spending of all bread-buyers would decrease, leaving aggregate income stable. While baker 2 may have different preferences to baker 1 (e.g. he may like chocolates vs candy), the shift in preferences would have only a small effect on the price level, given that chocolate prices will increase but candy prices will decrease.

As the above demonstrates, in order for demand to have an impact on prices (i.e. inflation) it would have to change consumer purchasing power as a whole. In other words, for this to happen, money in the economy needs to change. How is that possible? There are four major ways this could happen:

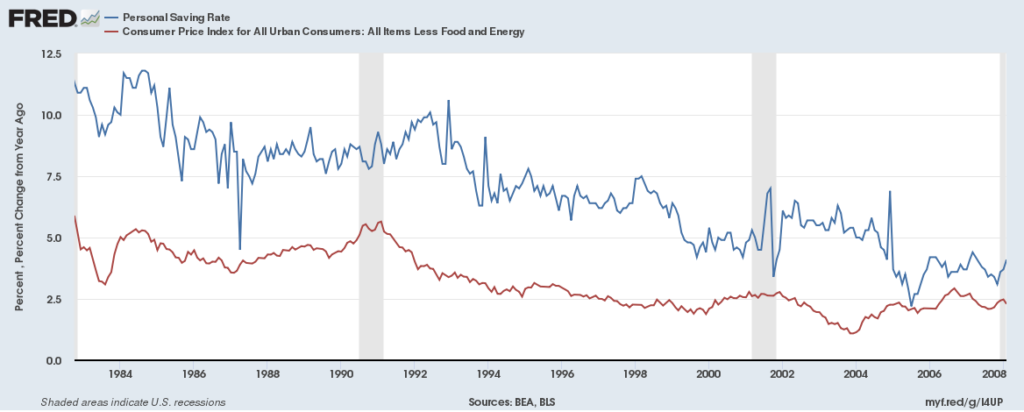

1. People Collectively Increase/Decrease Savings.

Most people, after getting their wages, put aside a percentage to save up for a rainy day. These savings percentage is, however, not stable across time, for reasons having to do with perceptions, availability of money and goods, and so on. The graph below illustrates the US experience, with the savings rate (blue line) being as high as 12% in 1955, reaching lows of 2.5% in 2005. As expected, if a higher percentage of income is spent, then money in the economy rises, with a subsequent increase in inflation (red line). Naturally, given that the US was not a closed economy at the time and that, as we will shortly demonstrate, other factors also play a role, the relationship is not clear-cut, even though the correlation between the two variables stands at an impressive 0.80. Note that availability of savings also has important indirect effects on money, which will be elaborated in the next point.

2. The Government Decides to Increase/Decrease Spending.

Suppose that the government decides that the construction of a new road would increase the citizens’ well-being. Note that the construction would come in addition to the usual expenses observed in the country’s budget. As such, construction company A will have more profits that year compared to previous years, without any other companies being adversely affected. As such, overall money circulating in the economy will increase. The government, in order to finance this project needs to borrow some money. This is usually done through the issuance on bonds, which are most often purchased by commercial banks, using customer deposits (i.e. people’s savings) to fund this purchase. As such, savings can also be indirectly used to increase money in the economy. However, note that this increase in money will likely not be permanent, given that the government will have to repay the bond and hence either increase taxation or decrease spending. Nonetheless, if money in the economy is growing for other reasons, an increase in taxation or a decrease in public spending will not have a large impact on inflation.*

3. Commercial Banks Increase/Decrease Lending.

Banks can create money by simply increasing the amount of lending they provide to the economy. Put simply, if someone wishes to purchase a house which costs $400,000 and does not currently have that money, then he can borrow and thus increase his purchasing power by that amount. Similar to the case of the government, the individual would have to repay the loan hence a reduction in his future spending will take place.*

4. The Central Bank Decides to Issue More Money.

This cause of inflation is the one which has caused most debate among economists over the past century. The idea is that, for some reason, the Central Bank decides that the economy needs some additional cash. What it could do then is simply “print” the money and spend it in a way that reaches the broader public. For example, it could finance government spending, meaning that the government would not have to borrow from commercial banks to fund its expenses. This is similar to what quantitative easing (QE) aimed at doing, i.e. the issuance of money to purchase government bonds. As you can imagine, actual (physical) printing of cash would mean that the Central Bank would permanently increase the amount of money in the economy. However, if the Central Bank purchases bonds, then it could sell them back to the private sector in the future and reduce the availability of money in the economy. Note that in order for such policies to be effective, the money needs to reach the private sector somehow; if banks decide against lending that money out then no actual change happens in peoples’ purchasing ability.

How about Supply?

Supply, in the case of inflation, relates mostly to producers increasing prices due to shocks which increase production costs, usually occurring for goods or services for which no close alternative exists at that point in time. For example, an unexpected increase in the price of oil would drive up prices for goods which are highly dependent on oil to be produced. A permanently higher oil price would cause a large one-off increase in inflation but the economy would, in the long-run, stabilise to the same level of inflation if the shock does not happen again, as discussed in a post about the natural rate of unemployment.

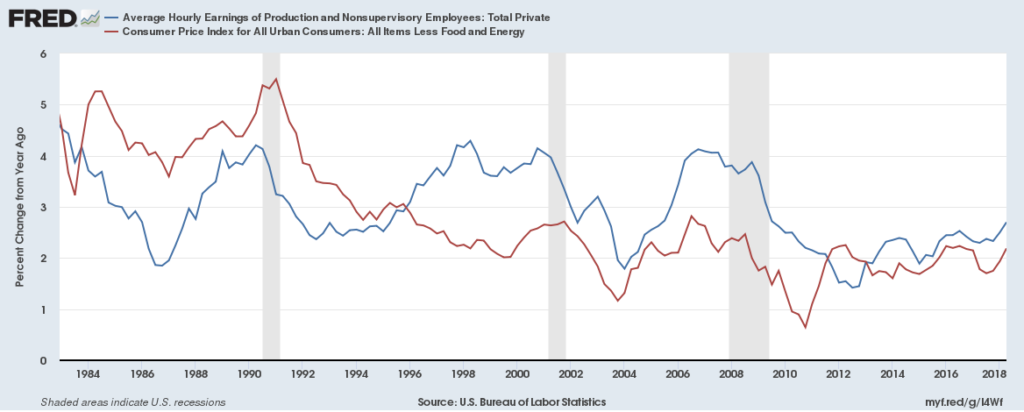

The wage example we have set before can be also partially used to illustrate a supply-driven effect on inflation. If the quantity of money is increasing due to demand factors, workers may request higher wages. If demand is increasing, firms can accommodate the workers’ requests and pass on, at least some part of this cost increase, to consumers by raising the price of their goods. The increase in the price will be counteracted with the overall increase in the quantity of money and hence the quantity sold will not decrease much, or even at all, depending on the respective growth rates of the two variables. Given that wages cannot always make a difference on their own, we do not expect them to be as directly related to the inflation rate as the savings rate. The figure below shows that even though a relationship appears to hold during some periods, it is not as strong as the inflation-savings rate one, with a correlation of about 0.36.

What changes in an open economy?

The major difference between open and closed economies, with regards to inflation, depends on basically two factors:

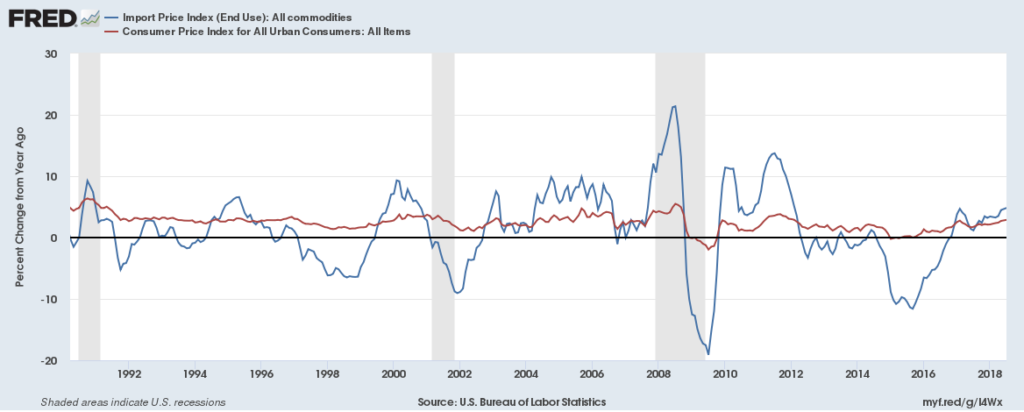

1. Imported Inflation

In a closed economy, we assume that all the materials required for the production of goods are produced/mined within the country. In the case of an open economy, goods can also come from abroad. As such, the price of goods abroad will have an impact on the price these goods are sold domestically. If a computer is sold for $500 abroad in January and then the price increases to $550 in February, due to worldwide demand surging, it would mean that the inflation rate for that particular category of goods would increase by 10%. This, naturally, depends on how important that good is for the domestic economy. As in the 1970s, if the price of oil increases internationally and our country is a net importer (i.e. imports more than it exports) of oil then we can expect a higher inflation rate. Note that in many countries, goods are imported so that they can be re-exported, and as such the effect from inflation does not stay within the country. Similarly, the amount of goods imported vs all goods changes over time and hence a constant relationship should not be expected. Still, and despite the larger volatility observed in import prices, the relationship appears to hold, with a high correlation of about 0.74.

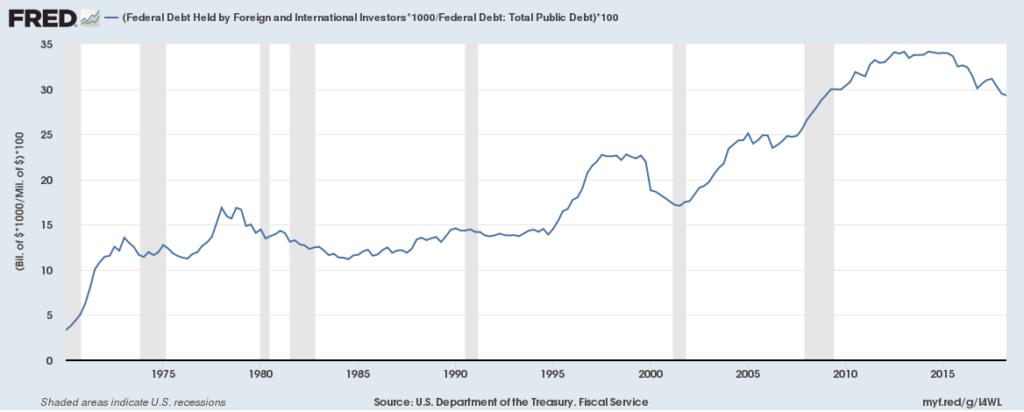

2. Capital Flows

The second distinction relates to an indirect effect. In particular, remember that increases in money supply tend to increase inflation. Suppose that the government decides to issue new bonds because it wants to spend some money on infrastructure. Even though domestic banks may not be willing to lend to the government, mainly because they are lending their money to individual borrowers and obtain higher yields, foreigners can perform such an action. The figure below indicates the percentage of US bonds held by foreigners which, as the reader may observe, has increased over time, increasing overall funding in the economy.

Naturally, capital inflows is not only related to public bonds. Foreign direct investment, related to large investments in the country (e.g. purchasing a house or building a factory), portfolio investment, related to smaller-scale investment (e.g. bonds or stocks), as well as deposits and loans by foreigners, can also have an impact, given that foreigners offer to exchange their currencies for the domestic one. This means that more money is channeled into the domestic economy, raising corporate profits (especially in the foreign direct investment case) and leading to higher wages and spending. The opposite can also hold: US residents can also invest in bonds and stocks abroad, raising inflation in those countries to some extent. As in everything, capital flows, mostly related to portfolio investment and deposits and loans can easily be reversed hence causing a drop in prices and tightening monetary conditions in the country.

What’s next?

Overall, this post has demonstrated what the theory behind the determinants of inflation is. In the coming post, we will see how, building on the theory bits above, traders can use economic announcements to gauge the direction of inflation. The last post of the series on fundamental analysis will relate to how economic growth can have an impact on currency. Stay tuned!

*Hardcore finance people would argue that the present value of the future tax cuts/decrease in spending would equal the amount of excess spending today; the same would hold for individual borrowing. Following this line of argumentation, it would mean that in that expectations of lower spending in the future should offset higher spending today. However, this would not always take place given the positive feedback loop and the overall euphoria which may be created following a (persistent) positive spending shock, either by the government or by borrowing. Further to this, short-run fluctuations in inflation will also occur despite the fact that they may diminish in the long-run.

Click here to access the HotForex Economic calendar.

Want to learn to trade and analyse the markets? Join our webinars and get analysis and trading ideas combined with better understanding on how markets work. Click HERE to register for FREE! The next webinar will start in:

[ujicountdown id=”Next Webinar” expire=”2018/09/11 14:00″ hide=”true” url=”” subscr=”” recurring=”” rectype=”second” repeats=””]

Dr Nektarios Michail

Market Analyst

HotForex

Disclaimer: This material is provided as a general marketing communication for information purposes only and does not constitute an independent investment research. Nothing in this communication contains, or should be considered as containing, an investment advice or an investment recommendation or a solicitation for the purpose of buying or selling of any financial instrument. All information provided is gathered from reputable sources and any information containing an indication of past performance is not a guarantee or reliable indicator of future performance. Users acknowledge that any investment in FX and CFDs products is characterized by a certain degree of uncertainty and that any investment of this nature involves a high level of risk for which the users are solely responsible and liable. We assume no liability for any loss arising from any investment made based on the information provided in this communication. This communication must not be reproduced or further distributed without our prior written permission.