The history:

There’s an important difference between what is known as “Great Britain” and the “United Kingdom”. The first is England, Wales, and Scotland, i.e. the whole larger island on the right of the above image, while the latter includes Northern Ireland, which is part of the smaller island on the left, comprising Ireland.

This was not always the case. Until 1927, when the Republic of Ireland became an independent state, this separation did not exist and the term “United Kingdom” essentially covered both islands. Without delving into the politics of the North-South divide, let’s just put it that, for a variety of reasons, Northern Ireland prefers being part of the UK while the Republic of Ireland wishes to be independent. Things were not always easy between the two, with troubles at the border, and an estimated 3,500 people dying during the 1970-1998 period before the Good Friday agreement was reached.

The current state of play:

Returning to the economics of Brexit, due to Ireland’s independence, and Northern Ireland’s choice to remain in the UK, the only place where the UK has a physical border with Ireland, and subsequently the EU, is where the two meet. As long as the UK is (or was) part of the EU, the exchange of goods and services between the two parts of the island is (was) almost restriction-free, as common market rules suggest that products do not need to be inspected for customs and standards.

Enter the backstop:

If (or once) the UK leaves the EU, the two parts of Ireland would be in a different customs and regulatory regimes, which would mean that products would be checked at the border. The issue is that neither the EU nor the UK would be happy with such a development.

From the UK point of view, this falls within its current red lines, i.e. that it seeks to regain border control and leave the customs union. As far as the EU is concerned, this “backstop” could only apply to Northern Ireland, i.e. that there is no point in the UK leaving the EU and still be able to trade freely with it. This is not acceptable for the UK as it would effectively set its customs and regulatory border in the middle of the sea between the two islands, thus limiting the extent of its power.

The problem is also more political than it appears: as the EU promoted the no-border issue between the two parts of Ireland, it was much easier to sustain peace in the region, as trade created the conditions for closer ties. If a hard border is re-established, many fear that it could reignite tensions, as the “unionists” would now not be able move freely across the island.

The proposed solution:

According to the European Commission’s November release, the two regions have agreed that the Irish backstop problem can be delayed until December 31, 2020, with no hard border taking place until then. This would effectively mean a continuation of the current common EU-UK customs territory, i.e. that the UK will still align its rules with EU legislation. By July 2020, the UK and the EU should ratify an agreement which would replace the backstop, either in whole or in part, by the December 31 deadline.

As of yesterday, the small concessions made by the EU, basically suggest that the UK and the EU have the right to raise a formal dispute against each other, if one party tries to keep the other tied to a no-backstop deal.

The future:

While these concessions appear to be legally binding, as Theresa May comments, it still remains to be seen whether they will actually make a difference, as the UK Attorney General comments that the UK would have no lawful ways to exit the arrangement; proving that the EU aims to keep the UK tied is quite subjective and thus difficult.

On the other hand, this would, in theory, provide an interesting solution for the UK, given that it can maintain both the customs union and also have its own power over the border/legislation/immigration. Still, hard Brexiteers would consider this a defeat since the decision was for a full-on separation from the EU.

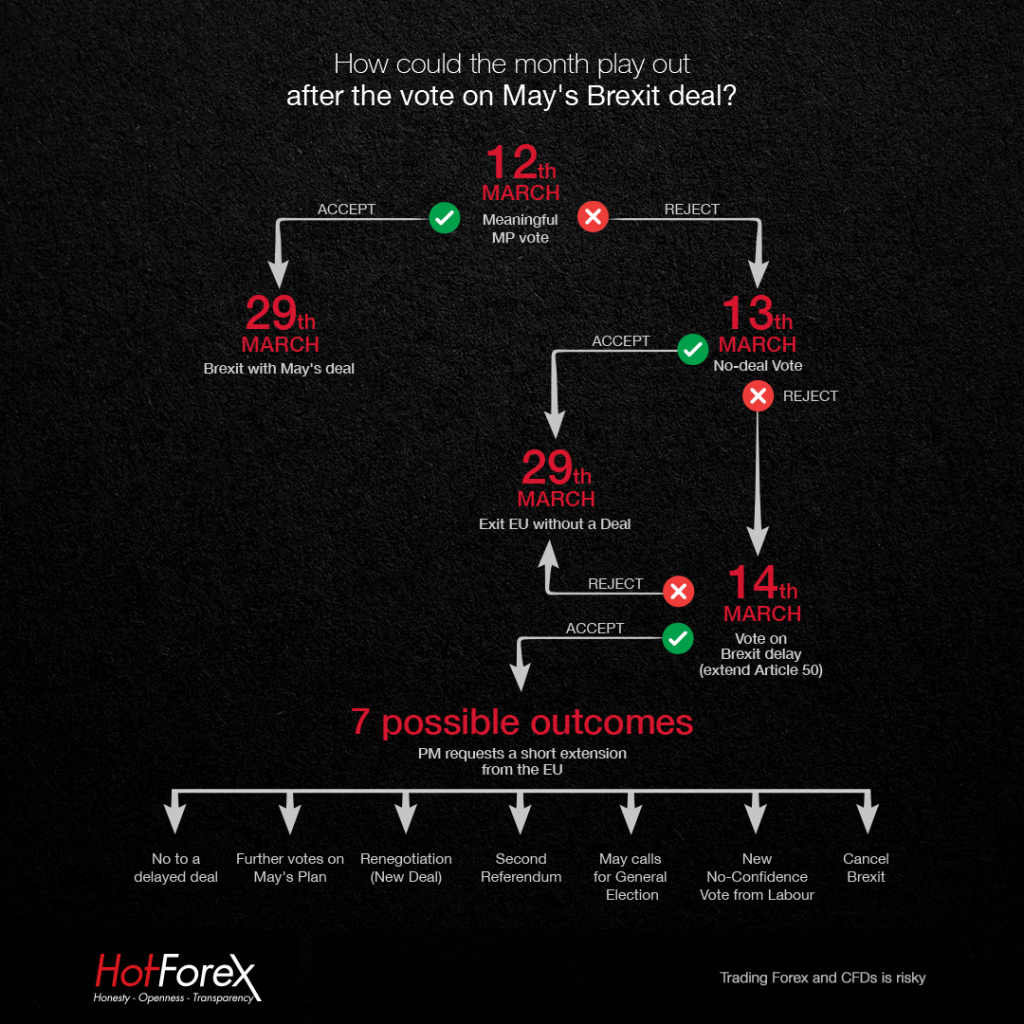

The only certainty is that there will be a vote today, which would have to see May’s revised agreement convincing 116 parliament members to switch sides in order to be accepted. Just to provide a glimpse of how difficult that would be, the estimated odds of the UK leaving the EU without a deal before April 1st have increased since the beginning of the month. If the deal is rejected again, then the next vote, which would take place tomorrow, would vote directly about accepting a no-deal Brexit.

Click here to access the Economic Calendar

Dr Nektarios Michail

Market Analyst

Disclaimer: This material is provided as a general marketing communication for information purposes only and does not constitute an independent investment research. Nothing in this communication contains, or should be considered as containing, an investment advice or an investment recommendation or a solicitation for the purpose of buying or selling of any financial instrument. All information provided is gathered from reputable sources and any information containing an indication of past performance is not a guarantee or reliable indicator of future performance. Users acknowledge that any investment in FX and CFDs products is characterized by a certain degree of uncertainty and that any investment of this nature involves a high level of risk for which the users are solely responsible and liable. We assume no liability for any loss arising from any investment made based on the information provided in this communication. This communication must not be reproduced or further distributed without our prior written permission.